Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig

- Din and Pesharah

Jewish law prescribes two different methods for courts to resolve disputes: din (strict judgement according to the letter of the law) and pesharah (court-imposed settlement).1 Under din, courts are instructed to decide cases by applying the substantive halakhot of Jewish civil law to the dispute at hand. Under pesharah, courts are instructed to resolve disputes by imposing a reasonable and fair settlement on the parties.2

- What is Pesharah: Pesharah Kerovah la-Din and Pure Compromise

What considerations would the dayanim bring to bear on a case being decided according to pesharah? Rishonim note that there are different forms of pesharah.3 One form of pesharah—sometimes referred to as pesharah kerovah la-din—tracks the equities as determined by the halakhah’s conception of who acted wrongly and how egregious their action was. Pesharah kerovah la-din differs from pure din in that it lowers the formal standards of evidence; it allows a beit din to issue an award based on moral wrongdoings (chiyuvim bidei shamayim and aveirot) that would otherwise not be justiciable or enforced in court; and it licenses dayanim to base their decision on authoritative halakhic opinions that are not accepted by a consensus of all poskim. On this view, the considerations in pesharah are mostly tethered to the equities determined by the core principles of Choshen Mishpat.4

A different kind of pesharah takes the form of pure compromise. Pure compromise pesharah is motivated by considerations of civil harmony (shalom) and looks to impose a settlement that will extinguish the dispute (le-hashkit ha-merivah) in a manner that will maximize the preferences and minimize the grievances of each party, even if the settlement significantly diverges from how the case would have been decided on its halakhic merits.5 Some commentators suggest that under this form of pesharah the dayanim are supposed to put themselves into the mindset of the parties and figure out the terms at which each party would be willing to settle.6

- Pesharah vs. Din

The Talmud records two opposing opinions whether courts should prefer pesharah over din or din over pesharah.7 One view maintains that it is prohibited (asur) for courts to do pesharah.8 This is because the courts are not permitted to deprive a litigant of what he or she is entitled to under the substantive provisions of halakhah. Depriving a litigant of their halakhic due constitutes a form of theft (gezel).9

The other view holds that courts are under an obligation (mitzvah) to do pesharah rather than din.10 The Rambam, Tur and Shulchan Arukh all rule that pesharah is preferable over din.11 And they each make a point of praising a court that frequently settles cases according to pesharah.12 Why should that be? Why should Jewish law be partial to resolving disputes according to court-imposed settlement rather than the letter of the law?

- Three Reasons Favoring Pesharah

Commentators offer several reasons why Jewish law favors pesharah over din. First, a court-imposed settlement has the potential to resolve the dispute in a manner that leaves both parties satisfied with the outcome, whereas din would usually leave one party dissatisfied.13 For similar reasons, pesharah can lead to a more stable resolution of the dispute because both parties will more likely comply with a pesak that has benefits for each of them, as opposed to a ruling that holds exclusively in favor of one side. These reasons underscore a beit din’s role in maintaining civil order through resolving conflicts and helping parties move on from their disputes. Chazal praise pesharah as a form of justice that incorporates reconciliation and enduring peace (“mishpat she-yeish bo shalom”).14

A second reason in favor of pesharah is that it allows the beit din to utilize a greater range of remedies than would be available under din.15 In certain areas of Jewish law, the remedies prescribed can be prohibitively limiting. For example, the standard for proximate cause in Jewish tort law (gerama be-nezikin patur) severely limits a plaintiff’s ability to recover damages in a tort action.16 Likewise, the pure principles of Jewish law do not allow a plaintiff to recover damages for libel or defamation suits.17 These limitations restrict a beit din’s ability to award damages as a matter of din, despite the fact that the defendant has acted wrongfully and even has a halakhic moral duty (chiyuv bidei shamayim) to compensate the plaintiff. Pesharah allows the beit din to consider such moral wrongdoings (chiyuvim bidei shamayim and aveirot) in its decision and to award damages accordingly.18

A third reason favoring pesharah over din is that pesharah can relax some of the procedural rules that govern a din torah. For example, under din, the plaintiff generally bears a heavy burden of proof. In some cases that burden requires a plaintiff to establish his claim through the testimony of two valid witnesses.19 Under pesharah, however, the dayanim can issue an award without valid testimony, based on strong circumstantial evidence.20

The common denominator to the last two reasons is that pesharah allows the beit din to consider wrongdoings that would otherwise not be justiciable or enforceable in beit din (either because of chiyuv bidei shamayim or because of the difficult burden of proof). While this benefits the plaintiff in allowing him or her to be compensated for a greater range of wrongdoings and at a lower standard of proof, it also benefits the defendant because the final award constitutes a comprehensive settlement of all matters pertaining the suit (including grievances and moral claims).

- A Beit Din’s Power to Impose Pesharah

Notwithstanding the ruling that pesharah is preferable to din, a beit din generally does not have the power to impose a settlement through pesharah unless it is authorized to do so by the litigants.21 This means that litigants would have to authorize the beit din to decide the case according to pesharah before the dayanim could impose a court-ordered settlement. One way to authorize the beit din is through the arbitration agreement. Indeed, many arbitration agreements are formulated so as to authorize the beit din to decide the case “either by din or by pesharah” (hen le-din hen le-pesharah).22

There is, however, one important exception where a beit din can impose a settlement without having been authorized by the litigants. When the substantive dinim of Jewish civil law are indeterminate with respect to the case at bar—when there is no clear halakhic resolution to the dispute—a beit din is empowered to resolve the case according to pesharah, even without the authorization of the litigants.23 This is because one of the roles of a beit din is to preserve civil order by resolving conflicts. It therefore has a duty to settle a case even when the substantive dinim of Choshen Mishpat provide no resolution. Poskim explain that in such instances din and pesharah converge, since din itself mandates that the court resolve the case according to pesharah when din is otherwise indeterminate.24 The din, in such a dispute, is court-imposed settlement.

- Brokering vs. Imposing a Settlement

How do we reconcile the fact that Jewish law prefers pesharah over din with the fact that, barring permission from the parties, a beit din generally does not have authority to do pesharah? Philosophically, the answer is that litigants have a right to din and are entitled to insist on it, yet halakhah still encourages them to waive their right in favor pesharah.25

Practically, the answer is that while a beit din generally cannot impose pesharah on the parties without the litigants’ consent, it has a duty to encourage them to accept pesharah. This has two procedural applications. First, when litigants appear before a court to do din, the court has a duty to offer the parties the option of choosing pesharah.26 According to some poskim, the court should even attempt to persuade the parties of pesharah’s virtues.27

Second, even when a court is accepted exclusively for din, the dayanim could propose a specific settlement to the parties and attempt to convince them of its benefits.28 Here the court is merely proposing a settlement, not imposing it on the litigants. Ultimately, the litigants have full discretion to decide whether they want to accept it.

- Conclusion

In conclusion, Jewish law favors pesharah over din. This is because pesharah provides for a more comprehensive resolution to the dispute. It allows the dayanim to consider wrongdoings that would otherwise not be justiciable or enforceable in court, and it allows the parties to move forward in a manner that has benefits for both sides. Although a beit din generally cannot impose a pesharah without authorization from the parties, it is supposed to offer the parties the option of pursuing pesharah. A beit din can even propose a concrete settlement in the course of a din torah, though ultimately it is up to the parties to decide whether they want to accept the beit din’s proposal. One exception is when din is indeterminate, in which case a beit din is empowered to impose a settlement on the litigants even without their prior authorization.

- Pesharah, Din, and Pesharah Kerovah la-Din at the Beth Din of America

The Beth Din of America’s standard arbitration agreement provides that the dayanim “may resolve this controversy in accordance with Jewish law (din) or through court ordered settlement in accordance with Jewish law (peshara kerovah la-din).” The Beth Din’s Rules and Procedures, Section 3(a), also provide that in the absence of an agreement by the parties, arbitration at the Beth Din will take the form of pesharah kerovah la-din.

As we noted above, pesharah kerovah la-din is different from the “pure compromise” conception of pesharah.29 A decision pursuant to pesharah kerovah la-din is constrained by the equities of the case as defined by the halakhah’s conception of right and wrong. What distinguishes “pure din” from pesharah kerovah la-din is that the latter relaxes the standards of evidence, allows the dayanim to issue an award for moral wrongdoings (chiyuvim bidei shamayim), and provides a framework in which dayanim can base their considerations on halakhic opinions that fall short of universal acceptance. In contrast to the “pure compromise” form of pesharah, the dayanim’s considerations in pesharah kerovah la-din are tethered to the equities determined by the core principles of Choshen Mishpat.

Although the Beth Din of America encourages parties to have their disputes heard according to pesharah kerovah la-din, the Beth Din’s Rules and Procedures, Section 3(b), provide for the Beth Din to hear cases either according to pure din or pure pesharah if that is the mandate of the parties.30

- Many thanks to Rabbi Shlomo Weissmann for comments and discussions that significantly enhanced this article.

Sanhedrin 32b, Mekhilta Yitro Parsha 2, Sanhedrin 6a-7a. - Aristotle also distinguishes between two different kinds of adjudication. He distinguishes between litigation according to the letter of the law and arbitration based on equity: “Equity bids us: to settle a dispute by negotiation and not by force; to prefer arbitration to litigation—for an arbitrator goes by the equity of a case, a judge by the strict law, and arbitration was invented with the express purpose or securing full power for equity (Rhetoric 1.13.1374b).”

English law also distinguished between courts of law and courts of equity. Courts of equity were more remedy-oriented and less bound by the formal rules that governed courts of law. See F.W. Maitland, Equity. For a broad discussion of equity in Jewish law, see Aaron Kirschenbaum, Equity in Jewish Law: Formalism and Flexibility in Jewish Civil Law (New York, 1991).

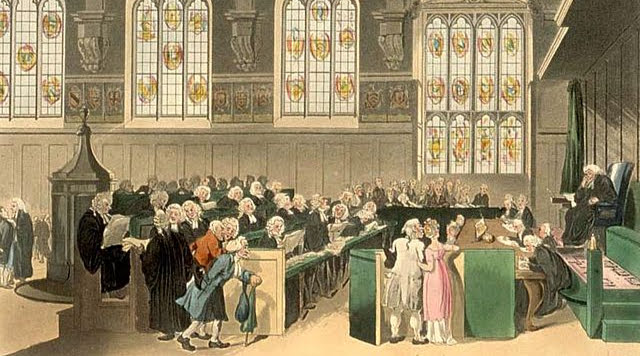

The engraving accompanying this blog post depicts the court of chancery in London, the body charged with deciding cases based on equity. Source information for the engraving is available here. - See for example Tosafot Ha-Rosh Sanhedrin 6a s.v. bitzu’a and Temim De’im no. 207. These Rishonim suggest that the plurality of pesharah types is implicit in the different names used for pesharah in the Talmud, Sanhedrin 6a (bitzu’a, pesharah).

- On pesharah kerovah la-din, see Shut Shevut Yaakov 2:145; Shut Divrei Malkiel 3:182; R. Zalman Nechemia Goldberg, “Shivchei ha-Pesharah” in Dinei Borrerut: Kellalei ha-Din ve-ha-Pesharah (Jerusalem 5765), pp. 263-269; R. Derbamdiker, Seder Hadin (Jerusalem 5770), Chapter 4, Sections 25-32; and R. Yoezer Ariel, Dinei Borrerut: Kellalei ha-Din ve-ha-Pesharah (Jerusalem 5765), pp. 154-259.

Some poskim add the further constraint that pesharah kerovah la-din cannot deviate in its final award by more than one third from what the decision would have been under pure din. See Shut Shevut Yaakov 2:145 and Pitchei Teshuvah Choshen Mishpat 12:3. See also Shut Divrei Malkiel 3:182.

For examples of pesharah kerova la-din decisions based on strong circumstantial evidence, see Shu”t Rosh 107:6 (allowing collection of a debt even though the promissory note was lost, given various extraordinary circumstances and the incomplete and suspicious answers offered by the debtor when questioned); Shevut Yaakov, 3:182 (discounting a valid promissory note signed by a father and presented by the creditor-son to his brothers in an attempt to collect the debt from the estate, since the note was more than 15 years old and, in letters written by the son to the father during those years, he repeatedly begged for money without mentioning this debt); Divrei Rivot 109 (discounting a promissory note on the basis of circumstantial evidence, ultimately granting $2,000 of an old, $3,500 promissory note); and Shu”t Maharashdam 367 (directing an arbitrator to make a partial award based on pesharah kerovah la-din for an old promissory note where no good reason could be proffered for failure to collect earlier). - See for example, Kenesset Ha-Gedolah Hagahot Beit Yosef, Choshen Mishpat 12 no. 15 (comparing pesharah to shudda de-dayni); Shevut Yaakov 2:145 citing Bava Batra 133b and Rashbam s.v. dayanei; Tosafot Ha-Rosh Sanhedrin 6a s.v. bitzu’a; and Temim De’im no. 207. (But see Divrei Malkiel 2:133, objecting to the idea that pesharah is a form of shudda de-dayni.)

For the role of pesharah in preserving social harmony and extinguishing disputes, see below Section 4 note 14. - Piskei Ha-Rid Sanhedrin 6a (“ka-asher yireh lahem mitokh ta’anoteihem kamah yimchol ha-tove’a ve-kamah yiten ha-nitb’a”).

Poskim also discuss other forms of pesharah, such as deciding a case according to the dayan’s sense of what’s correct or appropriate given the facts of the case and the individuals involved in the dispute. For example, Divrei Malkiel 2:133 refers to issuing a decision according to “yosher rachok min ha-din.” Nachalat Shiv’a (Shetarot, chapter 24) refers to arbitration agreements that provide for the dayanim to decide a case “kefi re’ot ‘eineihem.” Tosafot Ha-Rosh, Sanhedrin 6a s.v. ve-hacha, refers to a pesharah in which the dayanim decide based on “kol asher yeasher be-‘eineihem.” See also R. Derbamdiker, Seder Ha-Din, chapter 4 note 62.

For other formulations of pesharah, see Yad Ramah Sanhedrin 32b s.v. tzedek (“pesharah tzerikha ‘iyuna tefei u-le’ayein lefi shikul ha-da’at ve-lirot mi me-hen omer emet ve-al mi rauy le-hachmir yoter”); and Temim Deim 207 (“tzarikh omed ha-da’at livtzo’a ha-mammon u-lechalko be-midah shaveh shelo yehe echad mehem nifsad yoter mikhdei ha-rauy lo”).

For a criticism of “pure compromise” on the ground that pesharah should hew as close as possible to din, see Divrei Malkiel 2:133 (“ha-pesharah rauy le-tzaded kazeh she-yeheh karov la-din emet la-amito”). - Sanhedrin 6b-7a.

- R. Eliezer ben R. Yossi ha-Gellili in Sanhedrin 6b.

- Piskei Rid Sanhedrin 6b )“she-bitzu’a hu gezel, she-lokeach mi-zeh ve-noten la-zeh shelo ke-din”(.

Other commentators suggest that pesharah constitutes a violation of the court’s obligation to do justice through applying the Torah-mandated rules (dinim). See Shi’urei R. Shmuel (Rozovsky) on Sanhedrin 6b, and Meshekh Chokhmah Bereshit 18:19. - R. Yehoshua b. Korchah in Sanhedrin 6b.

- Tur and Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 12 (“kol dayan she-‘oseh pesharah tamid harei zeh meshubach”), Rambam Sanhedrin 22:4.

- See Tur Choshen Mishpat 12:4, Shulchan Arukh 12:2, Rambam Sanhedrin 22:4.

- Mekhilta Yitro, observing that in pesharah “sheneihem niftarim zeh mi-zeh ke-re’im.”

- Sanhedrin 6b, Zecharyah 8:16 and Rashi there. See also Shevut Yaakov 2:145 (“ikar ha-pesharah eino rak la-‘asot shalom bein ba’alei ha-dinim”); Meishiv Davar 3:10 (“im ha-din eino yakhol le-havi lidei shalom, ha-hekhrach la-asoto pesharah”; Shut Rosh, 107:6 (“natnu koach le-dayan lishpot ve-la’asot mah she-yirtzeh af belo ta’am ve-raya kedei latet shalom ba-‘olam”); and Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 12:3 (“mutar le-beit din le-vater be-mammon ha-yetomim chutz min ha-din kedei le-hashkitam mi-merivot”).

- Compare the common law distinction between equitable remedies and remedies at law. Equitable remedies provide the court with greater range of remedies than would be allowed at law. For the distinction between equitable remedies and remedies at law, see F.W. Maitland Equity.

- Bava Kamma 60a. See generally Ramban Kuntrus Dina De-Garmi and Rama Choshen Mishpat 386.

- Bava Kamma 91a. For remedies based on considerations other than the pure principles of tort law, see Rosh Bava Kamma 8:15 and Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 420:38.

- R. Zalman Nechemia Goldberg, “Shivchei ha-Pesharah” in Dinei Borrerut: Kellalei ha-Din ve-ha-Pesharah (Jerusalem, 5765) pp. 263-269, and R. Yoezer Ariel “Kellalei ha-Pesharah” in Dinei Borrerut: Kellalei ha-Din ve-ha-Pesharah (Jerusalem, 5765) pp. 187-195.

See also the Shulchan Arukh’s discussion in Choshen Mishpat 12:2 of imposing a pesharah payment in lieu of a shevu’ah obligation (“rashai ha-beit din la-‘asot pesharah… kedei liftor me-’onesh shevu’ah”). - See for example Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 408.

- R. Zalman Nechemia Goldberg, “Shivchei ha-Pesharah” (above n. 4) p. 263 and R. Yoezer Ariel “Kellalei ha-Pesharah” (above n.4) pp. 204-206. See also Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 15:5 and Bi’urei ha-Gra n. 24. For examples of pesharah decisions based on circumstantial evidence see above, note 4.

This discussion relates to the scope of a dayan’s discretion under din to issue a decision without perfect evidence. See Rambam Sanhedrin 24:1-2 and Netivot Hamishpat 15:2. - Kuntrus Ha-Rayot le-Riaz, Sanhedrin 5b; Piskei Riaz Sanhedrin 1:52,58. Note that the Talmud (Sanhedrin 6a) records a dispute whether the litigants need to perform a kinyan when authorizing the beit din to decide according to pesharah. Both opinions seem to agree, however, that the litigants need to authorize the beit din to do so. They disagree only on whether a kinyan is required.

- Nachalat Shiv’ah, Shetarot Chapter 24. For earlier appearances of this provision, see the citations in R. Yoezer Ariel, “Kellalei ha-Pesharah” in Dinei Borrerut: Kellalei ha-Din ve-ha-Pesharah (Jerusalem, 5765), pp. 156-158. Some poskim hold that because it has become standard to authorize the beit din to decide hen le-din hen le-pesharah, a litigant cannot request an arbitration to proceed only according to din. See Shut Tzitz Eliezer 7:48, Section 8.

- Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 12:5; Shut Rosh 107:6; R. Yoezer Ariel, “Kellalei ha-Pesharah” in Dinei Borrerut: Kellalei ha-Din ve-ha-Pesharah (Jerusalem, 5765), pp. 159-162 and p. 256.

- Shut Shevut Yaakov 1:109 (“de-kol she-ein ha-davar yakhol le-hitbarrer al pi ha-din, pesharah ba-zeh hayynu dino”).

- See Rashi Devarim 6:18 who interprets ve-asitah ha-yashar ve-ha-tov as the Torah’s exhortation to a litigant to accept pesharah over din. See also Bava Metzi’a 30b (and Kuntrus Ha-Rayot Le-Riaz Sanhedrin 6b), criticizing individuals for refusing to resolve their dispute according to pesharah and for insisting on litigating according to din (“he’emidu dineihem al din Torah”). See also Rashi, Shevu’ot 31a s.v. zeh (criticizing an individual who authorizes a lawyer (mursha) to litigate a claim on his behalf without also authorizing him to settle the claim according to pesharah).

- Sanhedrin 7a, Shulchan Arukh Choshen Mishpat 12:2.

- Derishah Choshen Mishpat 12:2, Sema Choshen Mishpat 12:6.

- Shakh Choshen Mishpat 12:6.

- See above, Section 2.

- The Beth Din’s Rules and Procedures acknowledge that in those cases where Jewish law mandates that pesharah alone provides the basis for resolving the dispute (see for example section 5 above), “no explicit acceptance of such shall be required.”